Tags for: On China’s Southern Paradise

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

On China’s Southern Paradise

Exploring treasures from the lower Yangzi delta

August 29, 2023

Appears in Cleveland Art, 2023, Issue 3

In advance of the opening of China’s Southern Paradise: Treasures from the Lower Yangzi Delta, Cleveland Art sat down with Clarissa von Spee, James and Donna Reid Curator of Chinese Art, interim curator of Islamic art, and chair of Asian art, to discuss the exhibition.

Beginning on September 10, the public will see China’s Southern Paradise: Treasures from the Lower Yangzi Delta in the Kelvin and Eleanor Smith Foundation Exhibition Hall. Why an exhibition about a specific region?

The idea of the exhibition is to make us aware that much of what we associate with the culture of traditional China today, such as silk and rice production, bamboo, green ware (called celadon in the US), color printing, garden culture, and landscape painting, originated from or flourished in the lower Yangzi delta. The core of this region in southeast China is smaller than Ohio! Like the US, China is a vast landmass, with great variation in climate and geography and a multiethnic population. While northern Beijing endures seasonal sandstorms from the Gobi Desert, southern Shanghai is washed by cleansing monsoon rains in the summer. The Yangzi delta, also called Jiangnan, which literally means “south of the [Yangzi] river,” includes the historical cities of Suzhou, Hangzhou, Nanjing, and Shanghai, which were all centers of trade, craftsmanship, and art production for centuries.

How did the region become such an important place in China? And how do we see that play out in the exhibition?

The lower Yangzi delta is geographically advantaged near the sea, with many natural waterways and a mild climate. These all facilitate the transportation and trade of goods, alongside fertile lands, lakes, and wetlands that create an agricultural wonderland. Cities play an important role, too. The water town Suzhou, for example, has over 300 bridges and canals and is called the Venice of the East. What the visitor will be able to see in the exhibition is how the scenery in paintings from 1000 to 1700 changes from vast riverscapes to cultivated rice paddy fields, populated with fisherfolk along lakeshores, and, later in time, to cities with traffic jams caused by boats moving in and out of the city gates.

Image

What caused this transformation of the landscape over many centuries?

An important historical factor is that the region repeatedly received waves of immigrants from the north that boosted the population, stimulated the economy, and caused the growth of cities, which in turn increased consumption, competition, and the production of the arts.

The reason for the construction of the Great Wall by China’s first emperor was effectively to deter the northern steppe peoples, whom the Chinese called “barbarians,” from invading China’s north. At each invasion, the imperial court fled south across the Yangzi, followed by parts of the population who would then settle in the south in the fertile Yangzi delta. This happened many times, notably in the 300s, 1100s, 1200s, and 1600s. Each of these times, the south received cultural impulses from the north. The exhibition evolves along these historic events.

What else will the visitors see in the exhibition?

The lower Yangzi delta is the region where the world’s earliest cultivated rice was found, and we have remains of Neolithic carbonized rice in the exhibition. Moreover, the China National Silk Museum has lent us a 12th-century young girl’s silk gauze dress along with bundles of raw silk threads of the same age. As bamboo grows abundantly in the Yangzi delta, the exhibition not only presents intricately carved bamboo objects but also shows an undershirt made of bamboo worn in the humid summer season from the museum’s collection. The garment was strung and sewn together from over 3,000 fine tubular bamboo segments.

Image

What are some artistic highlights that represent the unique culture and history of this region?

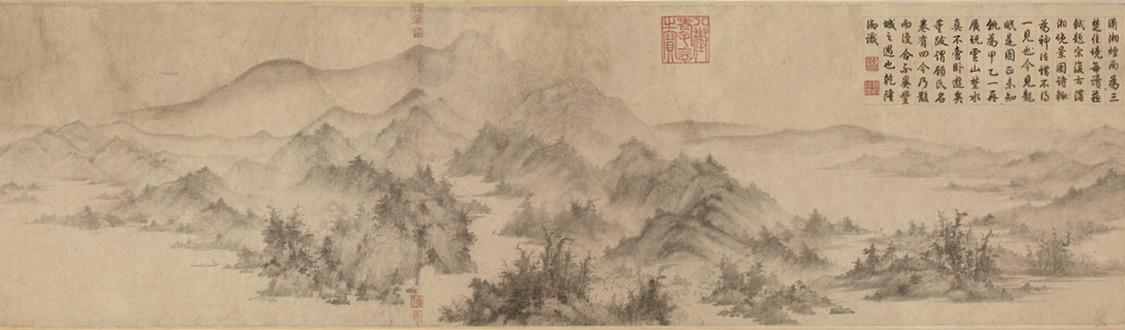

Artistically, we are fortunate to present a National Treasure from the Tokyo National Museum. This is a Chinese landscape painting depicting a mountain range shrouded in laces of mist and meandering waterways; the scene refers to a region at the confluence of the Xiang River and its tributaries in South China. The painting was conceived in the Yangzi delta and is at the same time an image of the Chan (in Japanese, Zen) Buddhist concept that everything is illusionary but the Buddhist truth.

We also show an elegant 12th-century set of gilded silverware used for tea, ice-cold summer beverages, and fruit, along with a delicately sculpted incense burner crowned by a Mandarin duck on a lotus flower, which both illustrate the high culture of well-to-do households in the imperial capital of Hangzhou and the Yangzi delta.

A must-see is an over-95-foot-long handscroll depicting one of the Kangxi emperor’s (reigned 1662–1722) southern inspection tours from Beijing via the Grand Canal south to Jiangnan. On loan from the University of Alberta Museums Art Collection, this painting is rarely seen and is one of a set that recorded the travels of the emperor to the south of the empire, where he visited historic sites, inspected water management sites, and met with people of various social levels. These paintings depict in fascinating detail the life of residents in the countryside and in cities of the lower Yangzi delta. One scene shows the emperor disembarking from his boat to be greeted by crowds of residents and countless officials who line the streets in the city of Suzhou.

Image

Why did you decide to mount this exhibition now at the CMA?

I am thrilled that this exhibition has finally come to fruition in Cleveland, as I had developed the concept for an exhibition celebrating the region of Jiangnan during my tenure at the British Museum in London. Having spent considerable time in this area in China, I came to realize the general lack of awareness of this culturally crucial region. This exhibition takes place in a time marked by political tension and a strained relationship between the US and China. The CMA and our six Chinese partner museums see a way to transcend and ease these tensions through cultural exchange, mutual understanding, respect for each other, and collaboration—all through the arts. This is perhaps the largest China-related exhibition at the CMA since Sherman Lee’s tenure. I hope that this exhibition encourages our institution to continue its century-old commitment to the arts of China and Asia. The exhibition brings over 200 art objects to Cleveland, and the CMA is its only venue. The works come from lenders in mainland China, Japan, the UK, Europe, the US, and Canada. Principal support is provided by long-standing donors of the museum, June and Simon K. C. Li and Gary Hoskins and Klaus Wagner from the MCH Foundation. Both parties have supported the museum in Chinese art for a long time, and their friendship and support are outstanding and particularly meaningful at this crucial moment.

Image